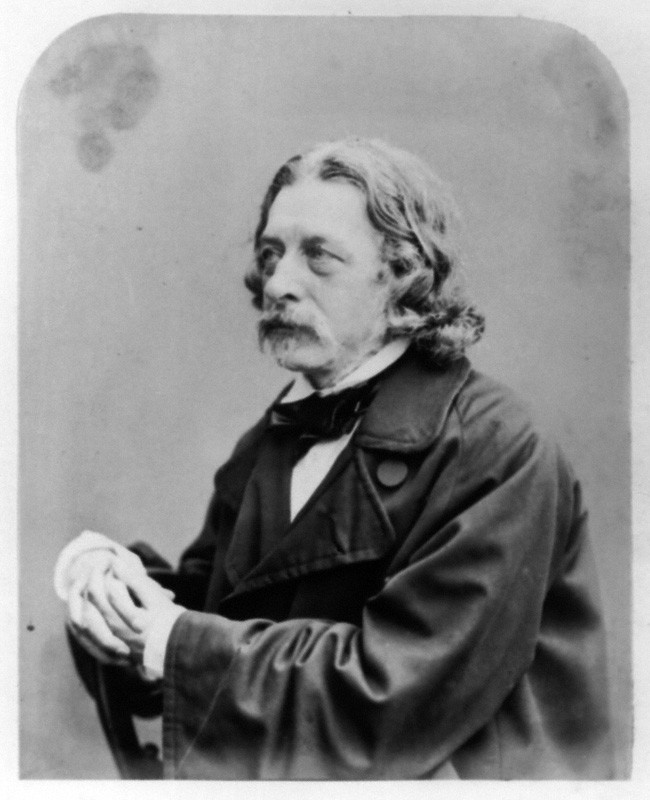

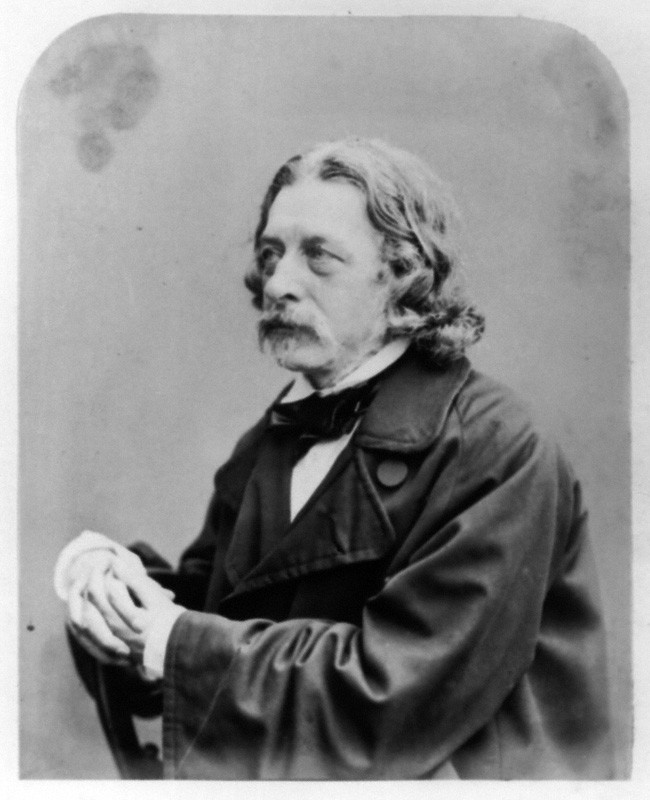

John Abraham Heraud on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Abraham Heraud (1799–1887) was an English journalist and poet. He published two extravagant epic poems, ''The Descent into Hell'' (1830), and ''The Judgment of the Flood'' (1834). He also wrote plays, and travel books.

Life

He was born in the parish of St Andrew's, Holborn, London, on 5 July 1799. His father, James Abraham Heraud, ofHuguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

descent, was a law stationer, and died at Tottenham, Middlesex, on 6 May 1846, having married Jane, daughter of John and Elizabeth Hicks; she died 2 August 1850. John Abraham, the son, was privately educated, and originally destined for business, but in 1818 began writing for the magazines.

Heraud had a large circle of literary acquaintances, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

, Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

, William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

, and John Gibson Lockhart

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of the seminal, and much-admired, seven-volume biography of his father-in-law Sir Walter Scott: ''Memoirs of the Life of Sir ...

. Southey was a correspondent, who thought Heraud capable of learning anything, except "how to check his own exuberance in verse", as he wrote to Robert Gooch

Robert Gooch, M.D. (January 1784 – 16 February 1830) was an English physician.

Life

Born at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, in June 1784, he was son of Robert Gooch, a sea captain who was a grandson of Sir Thomas Gooch. He was educated at a private ...

.

Heraud wrote for the ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River ...

'' and other reviews, and from 1830 to 1833 assisted in editing ''Fraser's Magazine

''Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country'' was a general and literary journal published in London from 1830 to 1882, which initially took a strong Tory line in politics. It was founded by Hugh Fraser and William Maginn in 1830 and loosely directe ...

''. There he was sub-editor to William Maginn

William Maginn (10 July 1794 – 21 August 1842) was an Irish journalist and writer.

About

Born at Cork he became a contributor to ''Blackwood's Magazine'', and after moving to London in 1824 became for a few months in 1826 the Paris correspond ...

, taking on literary criticism and philosophy. At this period he was still in partnership with his father, in legal stationery. The partnership was dissolved in 1841, when he went into the trade on his own in the Chancery Lane

Chancery Lane is a one-way street situated in the ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. It has formed the western boundary of the City since 1994, having previously been divided between the City of Westminster and the London Boroug ...

area, but unsuccessfully.

With the Carlyles Heraud was very close. Thomas Carlyle was well aware of Heraud assiduously cultivating favour, and of James Fraser's opinion that Heraud was "mad as a March hare", writing to Jane Carlyle about him in 1834.

Heraud edited ''The Sunbeam. A Journal devoted to Polite Literature'', in 1838 and 1839; the ''Monthly Magazine

''The Monthly Magazine'' (1796–1843) of London began publication in February 1796.

Contributors

Richard Phillips was the publisher and a contributor on political issues. The editor for the first ten years was a literary jack-of-all-trades, Dr ...

'' from 1839 to 1842; and subsequently the ''Christian's Monthly Magazine''. In 1843 he became a contributor to '' The Athenæum'', and later served as its dramatic critic until his retirement in 1868. From 1849 to 1879 he was also the dramatic critic of the ''Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

''. In 1869 he used that position to call for censorship of ''Formosa'', Dion Boucicault

Dionysius Lardner "Dion" Boucicault (né Boursiquot; 26 December 1820 – 18 September 1890) was an Irish actor and playwright famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the ...

's "courtesan play", prompting William Bodham Donne

William Bodham Donne (1807–1882) was an English journalist, known also as a librarian and theatrical censor.

Early life and career

Donne was born 29 July 1807; his grandfather was an eminent surgeon in Norwich. His father Edward Charles Donne ...

of the Lord Chamberlain's Office

The Lord Chamberlain's Office is a department within the British Royal Household. It is concerned with matters such as protocol, state visits, investitures, garden parties, royal weddings and funerals. For example, in April 2005 it organised the ...

to tighten up licensing of drama with sexual overtones.

In the late 1840s friends were trying to sort out Heraud's financial problems, amounting to insolvency; a fund-raising committee was formed, with officers John Forster, Thomas Kibble Hervey

Thomas Kibble Hervey (4 February 1799 – 27 February 1859) was a Scottish-born poet and critic. He rose to be the Editor of the ''Athenaeum'', a leading British literary magazine in the 19th century.

Youth

Thomas Kibble Hervey was born in Pai ...

and John Westland Marston

John Westland Marston (30 January 1819 – 5 January 1890) was an English dramatist and critic.

Life

He was born at Boston, Lincolnshire, on 30 January 1819, was son of the Rev. Stephen Marston, minister of a Baptist congregation.

In 1834, h ...

. On 21 July 1873, on the nomination of William Gladstone, he was appointed a brother of the London Charterhouse

The London Charterhouse is a historic complex of buildings in Farringdon, London, dating back to the 14th century. It occupies land to the north of Charterhouse Square, and lies within the London Borough of Islington. It was originally built ( ...

, where he died on 20 April 1887.

The Syncretics

Heraud was identified as a leading figure in the "Syncretics", a proto-aesthetic group mocked in ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'' and prominent around 1840.Nadelhaft, p. 629. After a few years the excitement around their eclectic approach subsided. A biographer of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

, who initially took a great interest, has called Heraud in particular a "general failure".

The group

Other Syncretics wereFrancis Foster Barham

Francis Foster Barham (1808–1871), known as the Alist was an English religious writer who promoted a new religion called Alism.

Life

The fifth son of Thomas Foster Barham (1766–1844), by his wife Mary Anne, daughter of the Rev. Mr. Morto ...

, Richard Henry Horne

Richard Hengist Horne (born Richard Henry Horne) (31 December 1802 – 13 March 1884) was an English poet and critic most famous for his poem ''Orion''.

Early life

Horne was born at Edmonton, London, son of James Horne, a quarter-master in t ...

, and John Westland Marston

John Westland Marston (30 January 1819 – 5 January 1890) was an English dramatist and critic.

Life

He was born at Boston, Lincolnshire, on 30 January 1819, was son of the Rev. Stephen Marston, minister of a Baptist congregation.

In 1834, h ...

. Barham and Heraud founded the Syncretic Society, or Syncretic Association. It grew out of an earlier group round James Pierrepont Greaves

James Pierrepont Greaves (1 February 1777 – 11 March 1842), was an English mystic, educational reformer, socialist and progressive thinker who founded Alcott House, a short-lived utopian community and free school in Surrey. He described h ...

, the "Aesthetic Society" or "Aesthetic Institution", based in Burton Street on the north side of Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

, with a core of Greaves and a few neighbours. Heraud and Barham took over the ''Monthly Magazine'', and it functioned as the organ of the group in the period 1839 to 1841. Camilla Toulmin gained the impression in 1841, visiting Horne, that there was a group of younger and ambitious men in the Syncretics, besides the better-known names. For example, the Syncretics took up the ''Festus'' of Philip James Bailey

Philip James Bailey (22 April 1816 – 6 September 1902) was an English spasmodic poet, best known as the author of ''Festus''.

Life

Bailey was born on 22 April 1816 in Nottingham, the only son of Thomas Bailey by his first wife, Mary Taylor. ...

.McKillop, p. 762 note 80.

Transatlantic ties

The group also found kinship with, and encouragement from, the New Englandtranscendentalists

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

. Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and av ...

corresponded with Greaves. He also sent books to Greaves and Heraud; Greaves sent back books including Heraud's ''Lecture on Poetic Genius''. Approval of the ''Monthly Magazine'' was strong from Alcott, Convers Francis

Convers Francis (November 9, 1795 – April 17, 1863) was an American Unitarian minister from Watertown, Massachusetts.

Life and work

He was born the son of Susannah Rand Francis and Convers Francis, and named after his father. His sister, Lyd ...

and George Ripley George Ripley may refer to:

*George Ripley (alchemist) (died 1490), English author and alchemist

*George Ripley (transcendentalist)

George Ripley (October 3, 1802 – July 4, 1880) was an American social reformer, Unitarian minister, and journa ...

. Heraud published one piece from New England in 1839, an oration by Robert Bartlett. It proved a false start, though. Later in the year the transcendentalists founded their own periodical, ''The Dial

''The Dial'' was an American magazine published intermittently from 1840 to 1929. In its first form, from 1840 to 1844, it served as the chief publication of the Transcendentalists. From the 1880s to 1919 it was revived as a political review and ...

'', along the same lines.

Writing in ''The Dial'' in 1842, Emerson in his article ''English Reformers'' praised Heraud as an interpreter of Jakob Boehme

Jakob may refer to:

People

* Jakob (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Jakob (surname), including a list of people with the name

Other

* Jakob (band), a New Zealand band, and the title of their 1999 EP

* Max Jakob Memorial A ...

and Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

; and referenced his papers ''Foreign Aids to Self Intelligence'', which had been announced as a three-volume work. Heraud took Emerson to be a disciple of Carlyle, and was contradicted in ''The Present''. A few years later he was explaining that Swedenborg was to be taken only as an example and inspiration, since the transcendentalist approach was at odds with an established church. It was through the pages of the ''Monthly Magazine'' that two notable Swedenborgians, James John Garth Wilkinson

James John Garth Wilkinson (3 June 1812 – 18 October 1899), was an English homeopathic physician, social reformer, translator and editor of Swedenborg's works, and a writer on Swedenborgian topics.

Life

The son of James John Wilkinson (died ...

and Henry James Sr.

Henry James Sr. (June 3, 1811December 18, 1882) was an American theologian, father of the philosopher William James, the novelist Henry James, and the diarist Alice James.

Following a dramatic moment of spiritual enlightenment, he became deepl ...

, came to know each other.

Carlyle in fact disapproved of the group around Heraud and Alcott House, Greaves's project. These included John Goodwyn Barmby, Newton Crosland, Horne, Henry Mansel, and James Elishama Smith

James Elishama Smith, often called Shepherd Smith (1801, Glasgow – 1857, Glasgow) was a British journalist and religious writer.

Smith studied at Glasgow University. Hearing Edward Irving preach in 1828, he became a millenarian and associated ...

.

Drama activism

A series of public lectures by the Syncretic Association started early in 1841. Bayle Bernard was one of the speakers, and the talks took place in the Suffolk Street Gallery, London. A circumstantial account, ''"Damned" Tragedies'', was given in the July 1842 ''Fraser's Magazine''. Bernard's talk was light-hearted chat about actors, but Heraud and Frederick Guest Tomlins addressed more serious aspects and limitations of current British theatre, before the weekly series outstayed its welcome at the Gallery. The Syncretics, who included alsoGeorge Stephens George Stephens may refer to:

*George Stephens (playwright) (1800–1851), English author and dramatist

*George Stephens (philologist) (1813–1895), British archaeologist and philologist, who worked in Scandinavia

* George Washington Stephens, Sr. ...

, became active in agitation to have unperformed drama staged. The context was the restriction in London to three theatres with patents, and an absence of new verse drama

Verse drama is any drama written significantly in verse (that is: with line endings) to be performed by an actor before an audience. Although verse drama does not need to be ''primarily'' in verse to be considered verse drama, significant portion ...

productions. Not short of ambition, the Dramatic Committee of the Association, through Heraud, pressed for a reformed and poetic theatre, an actors' joint stock company, and the performance of new work, as well as drama schools to elevate taste. A failed demonstration, ''Martinuzzi'' of 1841, written by Stephens, led to Heraud in particular being lampooned in ''Punch'', by William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

. The existing theatrical monopoly was, however, abolished by the Theatres Act 1843

The Theatres Act 1843 (6 & 7 Vict., c. 68) (also known as the Theatre Regulation Act) is a defunct Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom. It amended the regime established under the Licensing Act 1737 for the licensing of the theatre in Great B ...

.

Heraud himself wrote dramas and persisted. The tragedy of ''Videna'', based on Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

, was acted at the Marylebone Theatre in 1854, with James William Wallack

James William Wallack (c. 1794–1864), commonly referred to as J. W. Wallack, was an Anglo-American actor and manager, born in London, and brother of Henry John Wallack.

Life

Wallack's father was named William Wallack and his sister was name ...

; and ''Wife or No Wife'' and a version of Ernest Legouvé

Gabriel Jean Baptiste Ernest Wilfrid Legouvé (; 14 February 180714 March 1903) was a French dramatist.

Biography

Son of the poet Gabriel-Marie Legouvé (1764–1812), he was born in Paris. His mother died in 1810, and almost immediately after ...

's ''Medea'' were staged later.

Heraud as poet

''Harper's Cyclopædia of British and American poetry'' noted that as a poet, Heraud had been snubbed by the critics, "and not always unjustly". It also repeated the story attributed toDouglas Jerrold

Douglas William Jerrold (London 3 January 18038 June 1857 London) was an English dramatist and writer.

Biography

Jerrold's father, Samuel Jerrold, was an actor and lessee of the little theatre of Wilsby near Cranbrook in Kent. In 1807 Dougla ...

, asked by Heraud whether he had seen "his ''Descent into Hell''", and replying that he'd like to. Heraud made two attempts at epic grandeur in his poems ''The Descent into Hell'', 1830, and ''The Judgment of the Flood'', 1834. The view of '' Chambers's Cyclopædia of English Literature'' was that he attempted in poetry what John Martin did in art: the vast, the remote, and the terrible. It found his ''Descent'' and ''Judgment'' to be "psychological curiosities" of "misplaced power". George Saintsbury

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, FBA (23 October 1845 – 28 January 1933), was an English critic, literary historian, editor, teacher, and wine connoisseur. He is regarded as a highly influential critic of the late 19th and early 20th centu ...

put Heraud on a level with Edwin Atherstone

Edwin Atherstone (1788–1872) was a poet and novelist. His works, which were planned on an imposing scale, attracted some temporary attention and applause, but are now forgotten. His chief poem, ''The Fall of Nineveh'', consisting of thirty boo ...

, and above Robert Pollok

Robert Pollok (19 October 1798 – 15 September 1827) was a Scottish poet best known for his work, ''The Course of Time'', published in the year of his death.

Biography

Pollok was born at North Moorhouse Farm, Loganswell, Renfrewshire, Scotl ...

. Herbert Tucker regards the ''Judgement of the Flood'' as "deranged", but has more time for the ''Descent into Hell''. He places it with other, earlier attempts to dramatise Christian typology, such as those of William Gilbank and Elizabeth Smith of Birmingham. He notes Heraud's familiarity with Coleridge's apologetics, and his reference to Martin in the annotations.

Heraud later wrote a political epic, which remained unpublished. This work was under the influence of William James Linton

William James Linton (December 7, 1812December 29, 1897) was an English-born American wood-engraver, landscape painter, political reformer and author of memoirs, novels, poetry and non-fiction.

Birth and early years

Born in Mile End, east Lon ...

.

Works

Heraud was the author of: * ''The Legend of St. Loy, with other Poems'', 1820. * ''Tottenham'', a poem, 1820. * ''The Descent into Hell'', a poem, 1830; second edition, to which are added ''Uriel'', a fragment, and three odes. * ''A Philosophical Estimate of the Controversy respecting the Divine Humanity'', 1831. * ''An Oration on the Death of S. T. Coleridge'', 1834. * ''The Judgment of the Flood'', a poem, 1834; new ed. 1857. * ''Substance of a Lecture on Poetic Genius as a Moral Power'', 1837. * ''Voyages up the Mediterranean of William Robinson, with Memoirs'', 1837. * ''Expediency and Means of Elevating the Profession of the Educator'', a prize essay, printed in the ''Educator'', 1839, pp. 133–260. The other prize winners wereJohn Lalor

John Lalor (1814–1856) was an Irish journalist, author, and solicitor.

Early life and education

The son of John Lalor, a Roman Catholic merchant, Lalor was born in Dublin, and educated at a Catholic school at Carlow and Clongowes Wood College, ...

, Edward Higginson

Edward Higginson (9 January 1807 – 12 February 1880) was an English Unitarian minister and author.

Life

He was born at Heaton Norris, Lancashire, on 9 January 1807. His father, Edward Higginson the elder (b. 20 March 1781, d. 24 May 1832), wa ...

, James Simpson, and Sarah Ricardo-Porter.

*

* ''Salvator, the Poor Man of Naples'', a dramatic poem, privately printed, 1845,

* ''Videna, or the Mother's Tragedy. A Legend of Early Britain'', 1854.

* ''The British Empire'', written with Sir Archibald Alison and others, 1856.

* ''Henry Butler's Theatrical Directory and Dramatic Almanack'', editor, 1860.

* ''Shakespeare, his Inner Life as intimated in his Works'', 1865.

* ''The Wreck of the London'', a lyrical ballad, 1866.

* ''The In-Gathering, Cimon and Pero, a Chain of Sonnets, Sebastopol'', 1870.

* ''The War of Ideas'', a poem, 1871. Based on the Franco-Prussian War.

* ''Uxmal: an Antique Love Story. Macée de Léodepart: an Historical Romance'', 1877.

* ''The Sibyl among the Tombs'', 1886.

Heraud's knowledge of German was unusual; he was a follower of Friedrich Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

. He is also regarded as a disciple of Coleridge.

Family

On 15 May 1823 Heraud married, at Old Lambeth Church, Ann Elizabeth, daughter of Henry Baddams, and by her, who died at Islington on 21 September 1867, had two children, Claudius William Heraud of Woodford, andEdith Heraud

Edith Heraud (died 1899) was an English actress. Stage appearances included the Shakespearian roles Juliet, Ophelia and Lady Macbeth; she was also well known for giving readings of plays.

Life

Heraud was born in London, daughter of the dramatis ...

, an actress.

References

* Alan D. McKillop, ''A Victorian Faust'', PMLA Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep. 1925), pp. 743–768. Published by: Modern Language Association. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/457567 * Janice Nadelhaft, ''Punch and the Syncretics: An Early Victorian Prologue to the Aesthetic Movement'', SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900 Vol. 15, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (Autumn, 1975), pp. 627–640. Published by: Rice University. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/450016 * Fred C. Thomson, ''A Crisis in Early Victorian Drama: John Westland Marston and the Syncretics'', Victorian Studies Vol. 9, No. 4 (Jun. 1966), pp. 375–398. Published by: Indiana University Press. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3825817 * Frederick Wagner, ''Eighty-Six Letters (1814–1882) of A. Bronson Alcott (Part One)'', Studies in the American Renaissance (1979), pp. 239–308. Published by: Joel Myerson. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30227466Notes

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Heraud, John Abraham 1799 births 1887 deaths English literary critics English male poets 19th-century English poets 19th-century English male writers English male non-fiction writers